Self-Experimentation and the Four-Minute Mile

How medical students studying their own physiology did the impossible

Early in the 20th century, Michael P. Driscoll, himself a record holder for the indoor two mile, wrote a news article headline: “Mile Men Now Trying To Make It In Four Flat” (The Herald Statesman, 1909.) Run a four-minute mile?? Was it even possible? Many scientists said it was not. George P. Meade was a prominent chemical engineer (and formerly a record-setting thrower at NYU) who led the sugar refining industry. Meade also maintained a deep interest in the mathematics of athletic records. His paper published in The Scientific Monthly in 1916 began: “In June, 1915, Norman Taber, formerly of Brown University and Oxford, ran a mile in 4 minutes 12 3/5 seconds, about two seconds faster than any amateur had ever been credited with running that distance. The question may have occurred to some of us at that time, "How far can the breaking of records continue?"

Meade published mathematical analysis arguing that running records had approached a limit beyond which significant improvements were not possible.

Graphs and illustrations by Alan Heldman

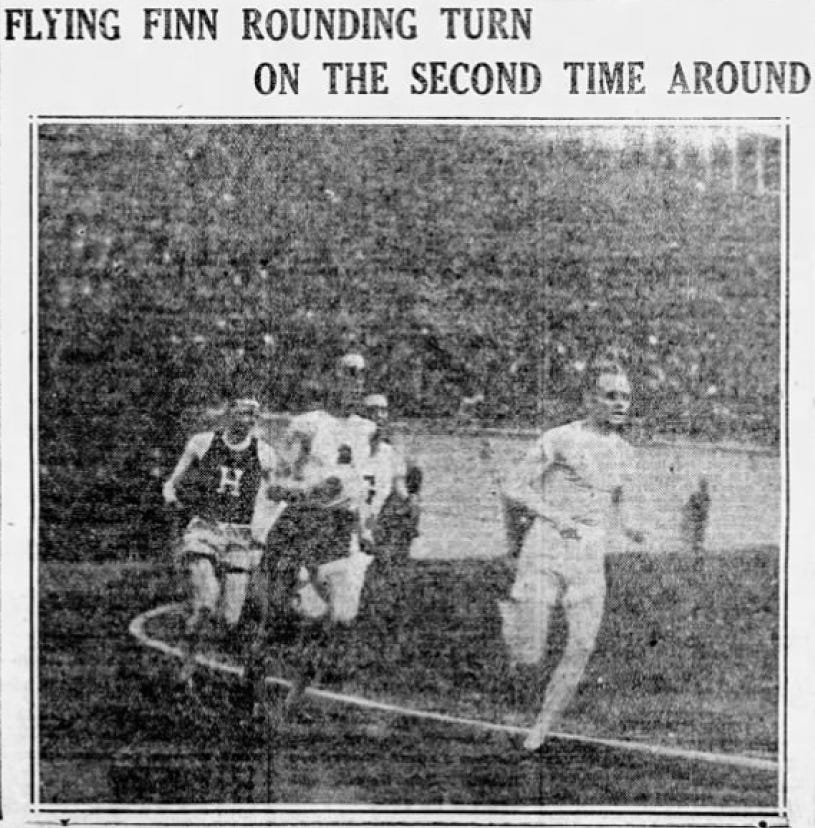

The greatest distance runner of his time, in 1923 Paavo Nurmi, the Flying Finn, held the world records at one mile, 5000m, and 10000m. After winning five gold medals at the 1924 Paris Olympics, Nurmi capitalized on his fame with a tour to race the top American amateurs. A 1925 headline asked “Four-minute mile for Paavo Nurmi?” An attempt on the record was set at Harvard, said to be among the fastest tracks in the world. Jaako Mikkola, who had coached the Finnish Olympic team and recently returned to Harvard as a coach specially prepared the track for an attempt for Nurmi to break his own world record of 4:10.4. It was front page news at the Boston Globe, right next to the news that Roald Amundsen was flying towards the North Pole!

Harvard Stadium filled with an overflowing crowd of 30-40,000 and thousands more pressed outside the fence to watch the famous runner. Alas, when it was done in 4:15.2 Nurmi could only say, “Wind, no goot.” Even worse for Nurmi, his American barnstorming tour and reports of payments on a subsequent European racing tour eventually led to his permanent suspension from the amateur-only Olympic Games.

Boston Globe, May 23, 1925

Whether the physiology of a human could ever achieve the four-minute mark continued hotly debated through the first half of the 20th century. In 1929, the great sportswriter Grantland Rice optimistically wrote “The mile is one of the greatest of all races, but it takes a terrific amount of hard work. It is a hard race because it calls for both speed and stamina. If the best half milers could hold the same pace for a mile the record would be around 3:42. This is beyond reason, but the time will come when some natural miler will get close to four minutes.”

A few weeks later, Rice’s newspaper column published a response letter from George P. Meade, the sugar chemist who believed that there were hard limits to human potential. Meade wrote “A study of the record books proves that such a performance is beyond the realm of reason. Back in 1886 W. G. George, the English professional, hung up a record of 4:12 ¾, and since then just two men in the world, Norman Tabor and Paavo Nurmi, have bettered that figure in outdoor competition. Through a span of 43 years, with all the thousands of mile races that have been run, just two runners have been able to cut under 4:13… In view of all these figures, Nurmi’s world’s record of 4:10 2/5 is an almost superhuman feat. To suggest that anyone will cut ten full seconds, or even five, off this figure is taxing the imagination… the only chance will be through the introduction of some stunt such as feeding the runner oxygen during the performance.”

The sportswriter Rice seemed to back down. “As heart and lungs are now made,” he admitted, “they could never stand the strain of a four minute pace without collapsing or running into serious results.” He was quite correct; to run faster, athletes would need to find a way to remake the function of their hearts and lungs. More precisely, they would need to increase the ability to take oxygen from the air and deliver it to the muscles.

A scientific approach to improving oxygen utilization would indeed prove to be the key. One noteworthy advance came from New Zealander Jack Lovelock. A Rhodes Scholar and medical student, Lovelock kept meticulous records of his training, nutrition, and results, and used photography to analyze his stride. While at Oxford he met fellow New Zealander/Rhodes Scholar/surgeon Arthur Porritt, who had won bronze in the 1924 Paris Olympic 100m depicted in the movie “Chariots of Fire.” Together, Lovelock and Porritt used their medical understanding of physiology to prepare Lovelock through the first half of the 1930s.

By the early 1930s, sporting news, film newsreels, and sports promoters around the world built up the question of the four-minute mile to a fever pitch. Lovelock was invited to participate in “The Mile of the Century” to be held at Princeton on July 15, 1933.

Boston Globe, July 12, 1933

With his methodical training regimen specific for the 1500m and mile races, Lovelock broke the world record at Palmer Stadium in 4:07.6, seven yards ahead of Princeton’s own William Bonthron who also went under the existing record. Lovelock took an extended break from running to focus on his medical training, but resumed running a few months before the 1936 Berlin Olympics where he won gold at 1500m.

The next big break towards the mythical four-minute barrier came from the Swedish team’s effort to fight back against the dominance of the Finns at cross country. Coach Gösta Holmér invented a training scheme called “fartlek” – speed play – running his team up and down grass and pine needle-covered hills, mixing fast bursts with relaxed intervals. Combining speedwork and stamina training in one session, the approach produced the two great Swedish milers Gunder Haegg (Hӓgg) and Arne Anderson, who lowered the WR back and forth, each breaking it three times between 1942 and 1945, from 4:06.2 in 1942 to 4:01.4 in 1945.

Of course, most strong young men were otherwise engaged during those years, but even still Haegg’s world record stood untouched for nine years after the war, leading to the conception among sports fans and milers alike that the four minute barrier was quite possibly just beyond the limits of human physiology.

Roger Bannister arrived at Oxford as a freshman in 1946, and recorded a mile in the Freshman Games at 4:53.0. In 1949, according to his own account, he learned about fartlek, and in 1950 he ran 4:14.8.

Like Lovelock, Bannister began to train in medicine and to consider every race as a self-experiment. “The self analysis which sport entails can be very helpful to the medical student” he later wrote in The Four-Minute Mile. In the Spring of 1951 Bannister worked in the Oxford physiology laboratory, conducting research on control of breathing and the factors leading to exhaustion. “The sprinter is born, not made” he argued, but the middle distance runner, limited only by oxygen uptake and oxygen transfer to the muscles, could be trained to improve. He put himself and other experimental subjects on a motorized treadmill, studying the limits of endurance. In the Oxford physiology laboratory he varied the room temperature, measured his own lactic acid thresholds, and experimented with techniques to improve the efficiency of his stride.

In April 1951 Bannister traveled to the USA to compete in the Benjamin Franklin mile at the Penn Relay Meeting, and on the same trip to learn techniques of gas analysis from the pulmonary physiology labs at University of Pennsylvania Medical School, among the best in the world at the time. He set a new meet record at the Penn Relay mile, winning in 4:08.3.

In September 1953, still a medical student, Bannister was invited to address a medical physiology conference in Liverpool. He reported his latest investigations on oxygen utilization and the limits of human running. The experiments he had conducted on himself, on other trained runners, and on untrained subjects showed him two things: 1) treadmill endurance could be dramatically extended by breathing 66% oxygen from a mask; and 2) specific training methods could increase the efficiency of oxygen uptake.

Mountain climbers had recently begun using supplemental oxygen, and on May 29, 1953, Edmund Hillary and Sherpa mountaineer Tenzing Norgay became the first climbers confirmed to have reached the summit of Mount Everest.

In June 1953 the sportswriter Jerry Nason wrote in the Boston Globe, “The four-minute mile is getting so close that you can taste it. It is track’s Mt Everest and has beaten more challenges… Gunder Hagg, a swift Swede badly in need of a haircut, has come closest – eight yards, or 4:01.4. That was eight years ago.”

Bannister’s publication in the Journal of Physiology

Sea level folks who travel to a high altitude destination are certainly aware that after some time, we become adapted to the lower oxygen concentration in the air. Bannister began taking breaks from running to climb mountains in Wales and Scotland. He took the speed play of fartlek and made it more precise, running repeat quarter-mile intervals. At one point he found that he could not maintain 60 second quarter mile intervals – but after a few days in the mountains with a break from running, he could run the same intervals more than a second faster. Among the last of the Oxbridge/Ivy gentleman amateur athletes who were able to study themselves as physiologists, Bannister refined his race strategy (including some advice from Jack Lovelock about when to surprise the competitors with a finishing kick) while building scientific confidence in the value of altitude training, of repeated intervals at race pace, and of taking recovery days – all techniques which are standard among middle distance racers today.

For his attempt at the four-minute mark, Bannister built a strong base of interval training, including sessions of 150 yard sprints repeated 15 times. April 12, 1954 he began running half-miles with three minute recoveries, repeated seven times. April 16-19 were spent climbing mountains in Scotland. April 22 he ran 10 quarter-miles at 58.9 seconds. And from May 1 to May 6 he rested completely.

May 6,1954 was a windy day at Oxford, but at the scheduled hour, the wind dropped. With his training partners to pace him, Bannister ran the quarter in 57.5, the half in 1:58.2, the three-quarters in 3:00.5, and the mile in 3:59.4. The crowd on hand and sports fans around the world went wild. The announcer for that race, Norris McWhirter, would go on the following year with his twin brother Ross to establish a new publication: The Guiness Book of World Records. And the first person to run a mile under four minutes suddenly became one of the most famous men in the world.

Sir Roger Bannister didn’t stop there, becoming one the world’s most eminent neurologists. The textbook Clinical Neurology published since 1960 was edited by Lord Russell Brain (really!) When Bannister took over as editor, the textbook was now called Brain and Bannister. He developed the emerging field of autonomic nervous system disorders, and brought the new technique of radio-immunoassay to the world of sport for detection of anabolic steroids.

As the 20th century ended, Hicham El Guerrouj established a 1999 mile world record of 3:43.13, which has remained unbroken now for more than 25 years. Is 2025 the year for another breakthrough? The early 2025 track season has already seen indoor records falling again and again. Rivalries among the middle distance runners -- Cole Hocker, Yared Nuguse, and Hobbs Kessler from USA, Jakob Ingebrigtsen from Norway, Josh Kerr from UK – along with improvements in both training shoes and racing shoes make many track fans hopeful that we will see that there is still no hard physiologic limit to human performance over the distance that captivated sports fans (and a few medical students) through the 20th century.

Great essay! Bannister story is crazy!

Fascinating story - thank you!