Short summary

In the articles here at “Thinking About Your Own Health,” I am working on an idea, about people curating their own health by owning their health data. To me, health data doesn’t just mean your medical records, cholesterol tests and vaccination history. The things you eat, do, breathe, and experience all can affect health. So if we could have that data too, might it help us learn to be healthier?

In this article, I divide modern American human nutrition science into three distinct eras:

1) Food as Fuel (~1890s -1945): Scientists worked on the question of how many calories a man or woman needs to do a day’s work.

2) Food as a Consumer Product (~ 1950 - 2005): Two forces – industrial food processing and marketing – produced the unhealthy human of the late 20th century.

3) Food as an Ideological and Tribal Battleground (2007 – present): Our attention and clicks are the product.

In this two-part article I am trying out an idea — that health data ownership can empower people to be healthier. I’m considering the food diary as a partial example of a Personal Health Record (PHR.)

Three Eras of Food in Modern America

1. The Era of Food as Fuel

Man is like a steam engine. The appetite is an occasionally defective fuel gauge.

In 1894 the US government offered its first official nutrition guidelines with a scientific approach to calories in (food) and calories out (human metabolism and work.) By laboratory combustion of various foods in an enclosed “bomb calorimeter,” the Wesleyan professor and USDA chemist Dr. Wilbur Olin Atwater pioneered measuring the energy content of fruits, meats, grains, and fats. In the lab across the hall, he measured the heat produced and oxygen consumed by workers in a large enclosed chamber, allowing him to calculate energy expenditure. Published by USDA as Farmers’ Bulletin no. 23, “Foods: Nutritive Value and Cost” advised that:

A quart of milk, three-quarters of a pound of moderately fat beef, sirloin steak for instance, and five ounces of wheat flour all contain about the same amount of nutritive material; but we pay different prices for them and they have different values for nutriment. The milk comes nearest to being a perfect food. It contains all of the necessary ingredients for nourishment, but not in the proportions best adapted for ordinary use. A man might live on beef alone, but it would be a very one-sided and imperfect diet. But meat and bread together make the essentials of a healthful diet.

Along with other American nutrition scientists at the dawn of the 20th century, including Booker T. Washington and John Kellogg, Atwater developed the field to optimize the nation’s nutritional supply chain, supporting booming industrial growth. Food was fuel for the work that needed to be done, and the planners’ job was to make sure that the workers got enough fuel. Consideration of the relationship between diet and the development of chronic disease would not come to dominate nutrition science until more than half a century later.

Atwater identified four principal classes of nutrients: protein, fats, carbohydrates, and minerals (such as salt.) He understood that the energy content of fats was higher than that of protein or carbohydrates. He also recognized that the nutritional value of food depended not on what was eaten, but on what was digested and absorbed. To study this, he weighed and analyzed “both the food consumed and the solid excrement” to determine the efficiency of digestion of various foods. Before Atwater, most scientific work on human nutrition had been performed in Germany, but his USDA report concluded that American workers needed more:

[The German] standard for a laboring man at moderately hard muscular work calls for about 0.25 pound of protein and quantities of carbohydrates and fats sufficient, with the protein, to yield 3,050 calories of energy. Taking into account the more active life in the United States, and the fact that well-nourished people of the working classes here eat more and do more work than in Europe and in the belief that ample nourishment is necessary for doing the most and the best work, I have ventured to suggest a standard with 0.28 pound of protein and 3,500 calories of energy for the man at moderate muscular work.

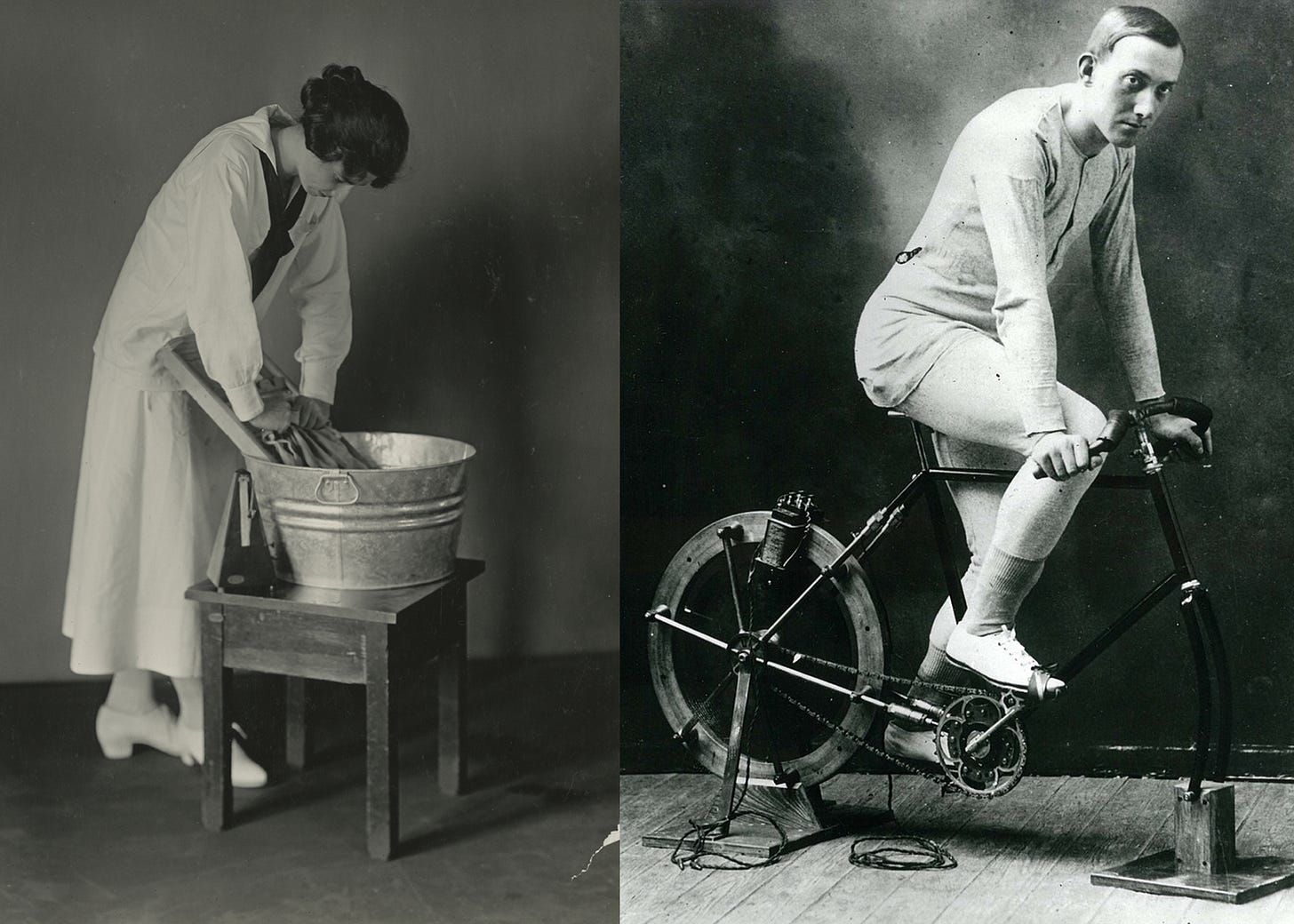

Figure 1 - Food is fuel: At the dawn of the 20th century nutrition science focused on the energy content of foods, and on the amount of energy required to fuel human labor. W.O. Atwater was a Wesleyan chemistry professor and USDA scientist who developed a scientific apparatus large enough to hold men and women while measuring the energy they consumed doing specific types of physical work.

Unknown photographers; circa 1907. “Calorimeter subject washing clothes, Washington D.C.” and “Subject on bicycle ergometer.” From the Wilbur Olin Atwater Papers, Special Collections, USDA National Agricultural Library.

2. The Consumer Era: Food is a Product.

Appetite is a behavior; businesses market to the behavior.

By the 1950s US nutrition became the science of commercial food production. Over the next 50 years, American consumers’ appetite for convenience, and the ability of the industry to produce food-like products with addictive qualities and stable shelf life led to many well-known health consequences, as chronic over-nourishment became possible, and in many cases inevitable.

Figure 2 - Food is a consumer product that looks like a TV.

I want to take a slight detour to consider this advertisement. Because my grandfather was a commercial illustrator who drew many magazine ads in the same era, I know pretty well the process used to draw this happy family in 1953. The work is unsigned, uncredited, but I have no doubt that whoever he or she was, it took the illustrator many years of practice and training to learn to draw like that. He may have attended art school where he learned human anatomy using a cadaver, just like in medical school. To make an advertising illustration like this took at least several days work, using multiple layers of tracing paper, pencils, erasers, and revisions; then inks and paints to produce a final, camera-ready art board. Besides the illustrator, the ad agency certainly had other specialists in copywriting, type layout, and color selection, each of whom earned a living practicing their special skill.

What’s the meaning of the illustration? I suppose the Mom’s fashion and hairstyle represent the fancy aspirations of the customer. The Dad is certainly not the sales target — he’s the least prominent figure with his tray balanced neatly on his knee. The Daughter has a good appetite and a big glass of milk, but her attention is glued to the TV. And the packaging of the TV dinner? It was designed to look like a television, complete with volume and channel knobs!

I think we all understand how the food industry contributed to the obesity epidemic, and so I will leave it at that and move on to my third era.

3. The Era of the Digital Native

The Consumer’s data is the product. The aggregation and interpretation of the user’s likes and clicks are sold back to the user through targeted products. Many people perform zero physical labor, and some exercise for health or appearance.

Here we are today. One hundred twenty five years after USDA measured food as fuel and humans as working machines. Seventy five years after food became a consumer product that looked like a TV. Today the most valuable companies’ products are based on the information that passes through our screens and eyes and clicking fingers.

Are we headed for a future where our bodies become even more useless in their contribution to our world and serve mostly as nodes in the network, as points of information and attention? Where likes, clicks, and then heartbeats are logged, and we burn calories walking 10,000 steps only as a gamified approach to preservation of the plasticized body, aspiring for “longevity?” Where some people burn calories primarily as a performance for their digital audiences? Where many of us have lost control of our bodies’ role in the domains of energy (over-nutrition) and information (hours per day sitting and scrolling.)

Figure 3 - The Consumer is a Product. The Era of the Digital Native.

The prompt “a person eating a snack while wearing a fitness tracker and VR goggles” was submitted to various image-generative AI applications (Adobe; Mid-Journey; Dall-E; Gemini; Chat-GPT; Canva.) More or less instantaneous results were assembled in a few minutes with Photoshop.

Today food is not just an industry but a battleground of ideology, and the power of many influencers for food ideas is a function of how many likes their surgically-enhanced and photographically-filtered appearance can get. Even people with medical credentials divide themselves into tribes based on ideas about food. The photogenic cardiologist’s Instagram says “You really must eat a plant-based diet.” The athletic surgeon’s TikTok says “You should really just eat ribeye and butter.” But they are both wrong. First, because an intellectually honest physician wouldn’t make a universal diet recommendation without knowing the risk profile and health goals of the person asking for advice. And second, because they shouldn’t be so certain that they are right anyway, given the limited evidence available to guide us on diet and health outcomes.

Limited evidence means that we should be modest in our conclusions. My modest guess is that for some people, their risk of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases is reduced by a plant-based diet compared to a cheeseburger diet. I’d also guess that for some people, that plant-based diet increases the likelihood of becoming frail as they age, and in any case is probably not ideal if their primary goal is to play offensive lineman for an NFL team.

Likewise, I’d guess that for some people, a very low carbohydrate/high protein and fat diet can help them shift at least temporarily away from metabolic disease and diabetes. But I am pretty sure that for some people on this diet, their cholesterol blasts off sky high — and I am suspicious that as a result some will need coronary bypass surgery in a few years. Not sure though. Even the best physicians’ ability to figure out which diet is optimal for which person and for which health goals is still in an early stage. The only way to improve this predictive guidance would be to have more data.

Can Data Help Us Regain Control?

Useless Bodies

The artist duo Elmgreen & Dragset explored our physical role in the digital world with a 2022 exhibition called “Useless Bodies?”

When our bodies no longer function as the main agents of our existence, we do not really know what to do with them. But Big Tech does. They gather somatic information and data on our daily routines while our interests and our movements are harvested by every app, program and screen we dedicate ourselves to. Our bodies mean business, as their data have become some of the most valuable products traded today. Our bodies might be useless because they are no longer needed for manual production, as in the 19th century or as consumers as in the second half of the 20th century -- though they might now, first and foremost, be useful as the products themselves, the providers of information that is repackaged and sold back to us in an endless loop of make-believe.

- Elmgreen & Dragset Useless Bodies? Fondazione Prada, Milan 2022.

The artists’ sculptures and installations depict various ways that our bodies have become useless. No longer producer, and only secondarily a consumer, today our physical selves support the digital transfer of information and attention.

Let me not get carried away imagining a nightmarish future where our bodies are just cells in the Matrix. Instead, let’s bring it back to the here and now, and think about what a person could do with their own nutrition data to improve their own health. To keep your body healthy, I’d argue, means to keep your body useful as a machine, able to do physical work. Data might help. In my practice as a cardiologist, some of the people who lived the longest, healthiest lives seemed to do it as maintenance engineers for their own bodies, carefully tracking inputs and outputs, experiments and results to optimize their own diet, exercise, and lifestyle.

Stay tuned. In Part II, I’m going to try to develop an idea about how we might improve health and make our bodies more useful by using our own nutritional health data. I’m headed to a couple of questions. (Questions where I’d genuinely like your opinion in the comments.) Would some of us be able to stay healthier if we had access to more and better data about ourselves in a highly detailed personal health record? And if it’s valuable, then who should own that data?

Another great article! The NFL Lineman point was effective.

I like where this is going. Definitely reminds me of the feelings (remember the Truth House ?) at Indian Springs.