This article is for you if you’ve thought about questions like these:

I don’t need to run a 4-minute mile, but I am out of shape and want to start exercising. Am I going to have a heart attack if I jog around the block?

I am 60 years old and thinking about getting back into training and competing. Am I going to drop dead if I try?

My cholesterol level was XYZ. Am I really at risk of a heart attack? Now my doctor wants me to take a cholesterol-lowering drug. Do I have to?

If you’re pressed for time, the quick-read summary is here.

Whether you are already in great shape, or you are just thinking about getting started, these are very good, seemingly simple questions. It’s not surprising that people want simple, straightforward, and confident answers. But there are very few simple answers where health is concerned. Much of the information you get from media sources, even well-intentioned ones, is useless (or worse.) Why? Because the only good answers to questions like these are based on a real assessment of your unique, personal risk profile.

When you exercise your heart muscle needs a lot more oxygen, so the rate of blood flow in your heart arteries (the coronaries) can go up 500%! Exercise is generally good for your health and reduces the risk of heart disease, but if you have atherosclerosis plaque in those arteries, the stress of intense exertion can also trigger a heart attack. This is the “exercise paradox.”

Illustrations: Alan Heldman copyright 2025.

I’ve spent most of my life studying heart and blood vessel diseases and teaching young doctors how to manage them – including how to answer questions like these. The more I learned, the more I realized that variability between one person and another makes it impossible to give a universal answer. Only by learning about the individual patient could I give them any useful advice — it has to be personalized.

My goal in these articles is to help you learn about yourself while identifying the better sources of information, using them intelligently for your own personal health goals. I think that almost everyone understands that the choices they make – what to eat, how to live – can affect their health. But a hard question for almost anyone is “Am I going to go seek some medical care and testing to look for trouble, even though I feel fine?”

So what about those questions? First, whether I am teaching a young cardiologist or just talking to my track and field pals, we need a firm grasp of the concepts of uncertainty and risk. These are core ideas behind making better choices. Uncertainty, because in health science nothing is ever 100% and there are no guarantees. You can do everything right and despite it all you still might have a stroke or get cancer. You can eat the wrong food and smoke cigarettes, and you still might possibly live to a ripe old age. It’s just that the influence of health choices can make the chances of those various outcomes very different.

Understanding risk is easy when it’s the weather, but a lot harder when it’s about ourselves. We all understand that when the weatherman says there is a 50% chance of rain – it might rain, or it might not. And there are different kinds of patterns that might all result in a 50% chance of getting wet. For example, there might be rain clouds moving overhead, and because they are patchy they might cross over your neighborhood, or might not. Or a different 50% risk pattern: the whole county is covered with clouds, but it’s just not certain whether the conditions will quite materialize for the water to precipitate out onto your head. Predicting the weather is complicated when the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil can affect what happens weeks later in Gainesville.

Am I a candidate to have a heart attack?

The same deal applies to a lot of the health questions I get asked. “Am I a candidate to have a heart attack?”

First the bad news: the only direct answer I can give is a weatherman-style response. And it’s even harder than predicting the weather. Even if I knew everything about you -- your blood pressure and cholesterol and family history and so on -- and even if I have looked inside your heart arteries with a gee-whiz nifty screening scanner -- all I can really tell you that you have a certain percentage chance of developing “atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD)” in the next 10 years. Middle-aged person with less than 5% risk? Many people would call that low-risk (but it’s still not zero.) What about a 20% chance of developing this disease in the next decade? Now that sounds to me like something where I would want to do everything I could to improve my odds.

ASCVD (atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease) means plaque in the walls of the arteries.

The good news is that it is pretty easy to assess that risk yourself using the Framingham Risk Score calculator.

The epidemic of cardiovascular disease

Before there was an Air Force One, the first presidential aircraft was a Douglas VC-54C Skymaster, modified with an elevator for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s wheelchair. Nicknamed the Sacred Cow, FDR flew on it only once, on the way to the Crimean resort town of Yalta. That’s where he met in February 1945 with Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin to plan the post-war administration of Germany and the establishment of the United Nations. Roosevelt’s blood pressure had been high for at least a few years, but in those days many doctors wrote it off as expected for a man of his age. Seeing Roosevelt at Yalta, however, Churchill's personal physician Lord Charles Moran wrote in his diary “the President appears a very sick man. He has all the symptoms of hardening of the arteries… I give him only a few months to live.”

“Hardening of the arteries” is exactly what it sounds like. Healthy blood vessels are pliable and elastic. Diseased arteries become calcified, with plaque-filled walls and areas of narrowing. Arteries with this disease can lead to a number of well-known complications. Depending on exactly which spots in your arteries are affected, whether the clogged spots get inflamed, and whether the inflamed spots form a blood clot, ASCVD can lead to chest pain, heart attack, heart failure, stroke, or sudden death.

Moran was correct: Roosevelt died two months later, with a blood pressure of 300/190 and a cerebral hemorrhage (a stroke with bleeding in the brain.) Just like over one-third of Americans, he died from cardiovascular disease. In the first years following Roosevelt’s death, the Truman administration funded national efforts to understand heart disease, including a study to try to determine what factors caused hardening of the arteries.

The most important study was conducted in just one town in Massachusetts. Clinical investigators examined a large sample of the adults in Framingham; the initial plan was to follow these subjects for 20 years. Over those 20 years, high blood pressure, diabetes, smoking, and blood cholesterol levels were found to be strong risk factors for developing heart disease. Though most schoolchildren know these facts today, before the Framingham Study the causes of heart and blood vessel disease were a mystery. By continuing to examine Framingham subjects for generation after generation, the study is now revealing genetic causes of heart disease clustering in families.

You can use the data yourself, to estimate your personal risk of cardiovascular disease. Try it for yourself here. You’re going to need to know your total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and blood pressure, and to know whether you are taking a “statin” cholesterol-lowering drug.

After defining the risk factors, the Framingham Study and others eventually went on to show that risk could be modified, creating an entirely new discipline of medicine called preventive cardiology. The risk calculator is highly influenced by your age, which is one thing that you can’t change. But the good news is that at any age, there are things you can do to shift your risk. Especially if your chance of rain / risk of heart disease is elevated, preventive strategies can significantly reduce the risk.

Sports-related cardiovascular problems around the world

In Italy it has been required by law since 1982 that every competitive athlete must have a yearly pre-participation evaluation – youth, young adult, and masters athletes alike must undergo mandatory yearly screening. The Italian data suggest that this approach has resulted in a significant reduction in the rate of cardiac arrest among their competitive athletes by detecting disorders that were previously not diagnosed. In one recent report from Italy, 1.9% of athletes ages 35-58 received a diagnosis serious enough to result in permanent exclusion from competition.

Most other jurisdictions are far less strict than Italy, even where cardiovascular disease is on the rise. In India, the move to a more urban lifestyle and diet seems to have been associated with a dramatic increase in the risk of coronary artery disease, heart attacks, and sudden death even in young adults. While it is difficult to compare data across different nations, the perception of an Indian cardiovascular crisis is supported by evidence that people with South Asian ancestry are at higher risk of developing disorders of metabolism which in turn lead to heart disease. Exercise, I suspect, is going to have to be a big part of India’s solution.

What about Masters athletes?

While high school and college sports in the USA have organized structures, often including trainers and team physicians, most masters athletes train on our own. Masters events barely have the resources to secure a location. When you think of all the road races, softball leagues, tennis clubs, and basketball courts, it’s just not realistic in America to expect uniform systematic screening for masters athletes. Unlike for the NCAA, there’s no governing body requiring pre-participation evaluation for masters.

To me, this reality leads to the determination that we (me and my elderly athletic friends!) have primary responsibility for making sure that we are doing what we can to identify and manage our cardiovascular risk. Before you decide to run a marathon, play a tennis tournament, or just start jogging, it’s up to you and you alone to decide whether you are going to ask for a check-up. And if you do, then what should your doctor do? Do you need an EKG (electrocardiogram — a tracing of the heart’s electrical activity)? Do you need an exercise stress test?

What should the pre-participation evaluation look like?

In 2001 The American Heart Association published its Recommendations for Preparticipation Screening and the Assessment of Cardiovascular Disease in Masters Athletes. This report did a particularly good job of explaining the “exercise paradox.” Here are two things which are both true:

Physical inactivity is an important risk factor for the development of coronary heart disease. Regular aerobic exercise may reduce the risk for heart attack.

…BUT ALSO:

Acute vigorous physical exertion (perhaps especially during competition) can trigger heart attack or sudden cardiac arrest. This is probably especially so in the presence of underlying heart disease, and in individuals who are not accustomed to regular exercise.

The 2001 AHA recommendations focused on the idea that a doctor at a pre-participation evaluation could identify some people with previously unrecognized heart disease, and could thus prevent some of those catastrophic events. No specific tests were recommended for everyone – not an EKG, or an exercise test. The recommendations were essentially to use clinical information like blood pressure, physical examination, family history, and any symptoms to decide whether to send folks for exercise stress testing. The 2001 document also included Guidelines for Disqualification, indicating that certain diagnoses would result in a physician-directed ban against participation in masters sports.

A later Canadian study subjected masters athletes to a more comprehensive set of pre-participation tests, including a Framingham Risk Score, an EKG, and a physical exam. Those who were found to have higher risk were sent on to have an exercise stress test or to see a sports cardiologist. Like the Italian approach, the study detected plenty of new problems. Despite yearly screening for five years, though, heart attack events still occurred among masters athletes. This result makes the same points that I taught my students for years:

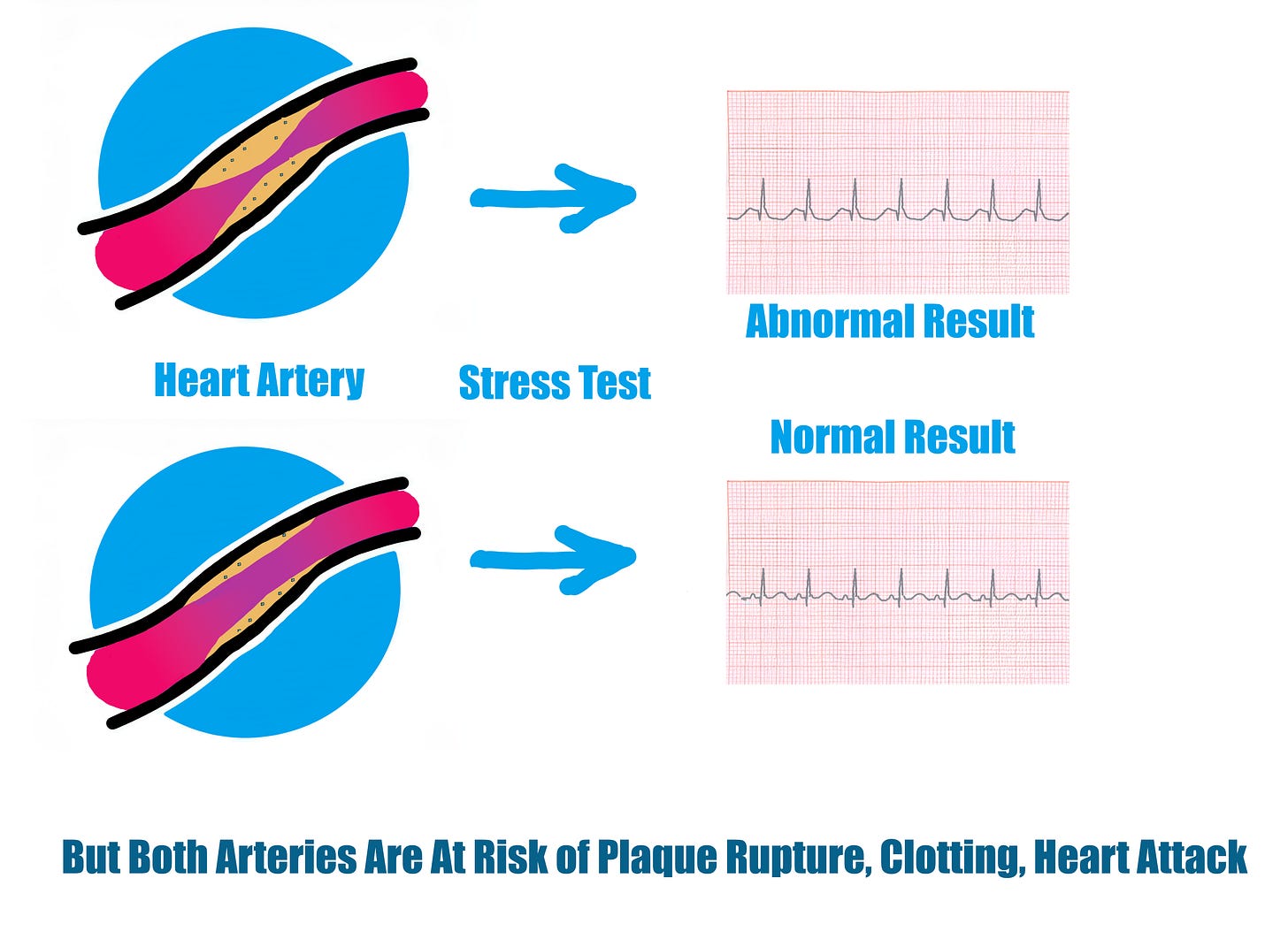

An exercise stress test is not a very good way to diagnose heart disease. Stress tests only detect when there are severe narrowings in the heart arteries.

It is very difficult to predict when heart attacks will occur. Heart attacks come when plaque gets inflamed, develops a blood clot, and suddenly closes the artery.

Mild narrowings are just as likely to get inflamed and cause heart attacks as severe narrowings.

Stress tests only detect when there are severe narrowings in the heart arteries. But heart attacks are just as likely to come from mild narrowings that get inflamed, develop a blood clot, and suddenly close the artery.

If a thorough Canadian check-up still doesn’t give me assurances that I won’t have a heart attack during exercise, what should I do?

Perhaps what we need is a way to look for disease in the heart arteries even if it isn’t causing severe narrowings.

My friend and colleague Dr. Arthur Agatston is a cardiologist specializing in prevention. He recognized decades ago that computed tomography (the “CAT scan”) could detect calcification in the walls of the heart arteries, and he developed a grading system now called the Agatston score. Because calcification occurs along with the process of ASCVD, it was soon realized that the Agatston score gave new information which complemented the Framingham Risk Score. A higher level of coronary artery calcification, reflected by a higher Agatston score, meant a higher likelihood of coronary artery disease, and of coronary artery events like heart attack. For the most part, this test is used together with the other clinical information like blood pressure, family history, and cholesterol levels, to decide whether someone should take cholesterol-lowering drugs.

I saw where I could get a scan for less than $100

Hang on. You may have noticed that hospitals in your area are offering these “Coronary Calcium Score CAT Scans” for a bargain price. Insurance companies generally do not cover them. Are the hospitals just being generous? Or are they counting on generating more downstream revenue when people have abnormal tests?

Most thoughtful cardiologists believe that if the calcium score is high, it should be used together with the other information to decide whether to prescribe cholesterol-lowering drugs. Most of us DO NOT believe that a high calcium score in a patient without symptoms should lead to rushing off to have stents and bypass surgery. But experience shows that this is hard to resist, and probably results in unnecessary surgeries.

Furthermore, when you CAT scan the chest you might very well find other things, like nodules in the lungs, leading to panic about lung cancer and additional testing. So if you are going to have this (or any other) test, you’ve really got to be ready with a plan for what you’re going to do with the results, even unexpected findings. If you buy into my thesis that a thinking person ought to understand their own health and use good information to make decisions, then where can we get that good information?

Just in time to help comes a brand new 2025 review from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology, “Clinical Considerations for Competitive Sports Participation for Athletes With Cardiovascular Abnormalities.” It’s a big, thorough document of 50 dense pages. Eleven sections representing eleven task forces. 49 genuine expert authors. 273 references. Here, my friends, is the best, most up-to-date information you are going to get, including an entire section on master athletes with cardiovascular conditions.

If you’re up for it, the full document is here. It covers all sorts of conditions including atrial fibrillation (AFib) and other arrhythmias, people who’ve already had heart attacks or coronary artery stents or surgery, other causes of heart muscle scar or abnormal function, valvular heart disease, aortic diseases, genetic cardiac conditions, and many others. Because it is such a complete report, here I am just hitting some highlights that are applicable to the questions I posed at the outset.

A physical examination is still useful to detect things like high blood pressure and heart valve problems. The pre-participation cardiac evaluation now includes that an EKG test can be helpful but only if it is interpreted by a doctor who understands athletes’ hearts, and if there is access to follow-up testing needed to sort out the false positives.

Different sports challenge strength and endurance in widely different ways and this affects the cardiovascular risk of different types of athletic events.

Models like the Framingham Risk Score were developed in a general population and have not been validated in masters athletes. It is likely that habitual exercise reduces our risk, but does not eliminate it.

Then, to make it even more complicated, masters endurance athletes with many years of high-volume aerobic training seem to be more likely to develop calcification in their heart arteries. So when calcification is found in people who’ve done a lot of long-distance, it probably indicates a somewhat lower level of risk than the same degree of calcification in a sedentary person.

So am I getting that CAT scan or not?

The document says that if you are a masters athlete and otherwise low-risk for ASCVD, you should probably not undergo advanced testing like a CAT scan. In this regard, “low-risk” means a risk score of less than 5% chance of ASCVD in the next 10 years.

But masters athletes with intermediate or high risk should

Learn about and adopt lifestyle changes (diet, alcohol, stop smoking) and follow guidelines about who should start preventive treatments like cholesterol-lowering drugs.

Learn about symptoms that might indicate heart disease so that they can get prompt attention if something comes up.

Consider further testing to assess their risk, including with a Calcium Score CAT scan, a maximal-effort exercise stress test (with or without imaging), or the fancier, more expensive CAT scan called coronary CT angiography. These tests might be reassuring; for example, a calcium score of zero would be considered by many doctors as a point against prescribing a cholesterol-lowering drug. But these tests might also suggest higher risk, and lead to a recommendation for more intensive treatment, or even a reconsideration of whether the risk of intense athletic competition is acceptable.

In general, the new approach does not say that a certain diagnosis disqualifies athletes from participation. “Shared decision-making” is the way things should now be done, discussing the risks among patient, doctor, and other stakeholders, to arrive at a joint decision. For specific cardiac conditions, the scientific statement gives information about the level of risk that doctors and patients can consider as they decide whether to continue participating in the sport despite their diagnosis.

But I take a baby aspirin so I’m OK, right?

Low dose aspirin is an important and powerful drug for patients with certain ASCVD problem; it saves lives in people who have had a heart attack. But the use of aspirin for primary prevention (meaning trying to avoid that first heart attack) has been found to be of very little marginal benefit, and comes with a clear increase in the risk of bleeding, including serious bleeding.

If you are taking aspirin or other blood thinners, the new guideline document helpfully categorizes different athletic activities for their risk of impact and collisions, which would translate into the risk of trauma and bleeding.

Sudden Cardiac Arrest: Risk for masters athletes, and why the environment matters

For my friends already pushing themselves to the limits of their age groups in masters athletics, it can feel quite personal to see on-field sudden cardiac arrest events like affected college basketball player Bronny James and professional football player Damar Hamlin. Sudden cardiac arrest can occur even in young and exceptionally fit athletes. When it happens in young people, the underlying cause is most often related to genetic or congenital conditions (ie, abnormalities that were present since birth.) Exercise-related cardiac arrest in older participants, on the other hand, is most often a consequence of ASCVD, and this can occur even in people who have never had any signs of symptoms of heart disease. How often does this happen? Data on the event rates in masters are remarkably hard to find. But lots of cardiologists know about a “middle-aged patient who passed a stress test, then dropped dead in the gym a week later.”

In the case of James and Hamlin, quick emergency efforts saved their lives and they returned to playing at the highest level. This did not happen by accident. In both cases, a chain of emergency care was present because it had been built-in to the organization of the sport. Even a comprehensive program of pre-participation screening does not eliminate the risk of cardiac arrest during exercise. To make participation safer, the 2025 update specifies that programs can and should provide effective emergency action plans, including:

Prompt recognition of cardiac arrest

Personnel trained to provide effective CPR

Immediate availability and use of an AED (automatic external defibrillator)

A coordinated medical transport system to a defined facility

The emergency care programs should be developed, practiced, and used for all environments where competitive athletes train and compete.

Outside of the sports world, we know that outcomes with cardiac arrest are best in certain locations like casinos and airports where there are a) a lot of people, b) a high degree of oversight, c) relatively high event rates (perhaps because both casinos and airports attract older folks at risk of heart disease, and then trigger cardiac events by providing highly stressful situations!) With their high event rates and close-monitoring by authorities, casinos and airports can both provide quick access to trained responders who have automatic defibrillators.

This observation does lead to the question of whether we masters athletes are doing everything we can in the places where we exercise and compete. While we can’t expect event organizers to coordinate everyone’s pre-participation risk assessments, I think it is reasonable to expect an emergency action plan at sporting events, including personnel trained in CPR, availability of AEDs, and a plan for medical transport.

Thinking About Your Own Health should not scare you. Done right, it should make you safer. Consider your own risk. Consider whether you want help defining it further. I hope you are lucky enough to have access to someone who is expert at helping, and at thinking with you about whether there are things you can do to reduce your risk. I will see you at race time!